III. B. 1. b) A new representation of motion In

III. B. 1. b) A new representation of motion

In 1878, British photographer Eadweard

J.Muybridge, who worked for the American government, proved, with the help of

instantaneous photographs, that at some point in a horse’s gallop all its legs

were off the ground at once and thus demonstrated that the dominant opinion at

that time was false. Put in a zoopraxiscope, another invention of Muybridge

which worked as a primitive version of later

motion picture devices, still photographs were shown in rapid succession and

created the illusion of movement.

Ten

years later, Louis Aimé Augustin Le Prince (1842-1890), a Frenchman who moved

to Leeds in West Yorkshire, England in 1866, shot the allegedly first motion

picture, known as Roundhay Garden Scene.

In 1895, Auguste and Louis Lumière presented La

Sortie de l’Usine

Lumière à Lyon

in a public projection and inaugurated the cinematograph, the ancestor of the

video camera.

All

these progresses altered the photographic vision of movement in the

photographers’ mind. Through jerky movements the human eye’s vision of movement

was being better represented.

However, Alvin Langdon Coburn’s Vortographs and the use of blur

corresponded to Etienne-Jules Marey’s studies or Thomas Eakins’s studies of

motion rather than to the cinematographic perception of it.

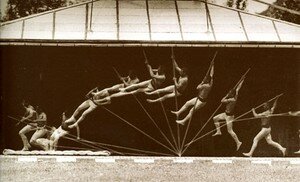

Etienne-Jules Marey was a French physician who was

first interested in the notion of motion inside the human body, like the blood

circulation for example, but who quickly studied the motion of the human body

itself. To describe and analyse the human walk and to a larger extent any kind

of motion, he developed a chronophotographic technique. In 1882, the

chronophotograph was officially born. He liked to call it his “photographic

gun”.

As opposed to Muybridge who used several

cameras or lenses that he placed alongside a platform to capture the gallop of

the horse, Marey used the same camera with a rotary shutter and really short

times of exposure to produce the illusion of motion.

Etienne-Jules Marey, Mouvement du

saut à la perche, around 1890

In his book entitled Art and Photography, Aaron Scharf reported,

“The resulting images, though lacking the

clarity of those by Muybridge, surpassed them by showing each phase of the

movement in its correct spatial position relative to all other phases recorded

on the same plate. Furthermore, the contiguous and superimposed images of the

chronophotograph revealed the continuity patterns of the movement itself.”[6]

Two conspicuous aspects of the use of blur can thus be distinguished: a continuous blur and an interrupted blur.

A first aspect of the blur, the continuous blur is mostly pictorial and

is carried out in a continuity of time. From a time marked T1

to another time marked T2, the shutter is

continuously opened. A graphic representation of the continuous blur would be a

straight line: T1 ---------- T2. A second

aspect of the blur, the interrupted blur is carried out in a continuity of time

but, as opposed to the continuous blur, a time scattered in portions. From T1

to T2, the shutter briefly opened in a repeated and regular

way causing interruptions. Thus, a graphic representation of the interrupted

blur would be a scattered line: T1 - - - - - - T2.

Yet exactly the same space is apprehended differently. In the sense that,

as far as Marey’s scientific and Coburn’s artistic pictures are concerned,

space seems to slide whereas it is either the subject or the camera which

slide. In a pictorial use of blur, space does not seem to move since the continuity

of pose gives the impression of a stabilized space.

In

the 1880s, as Pictorialism emerged, a new representation of motion was set with

the improvements of the camera. As time of exposure reduced and optical systems

improved, scientists studied the evolution of movement in time and succeeded in

breaking up the different phases of movement. Alvin Langdon Coburn was one of

the rare amateur photographers to use scientific processes in an artistic way.

Nevertheless, the debate between art photography and science photography was

still vivid and animated. A profound gap was still standing between the two. It

was not until the war of Vietnam, at the cusp of the 1960s and 1970s, and the introduction

of television in every home that document photography reached the status of art

photography and found its ways to galleries. As war photographers acceded to

the status of authors and document photography was directly exhibited, instead

of being reproduced in magazine like Life

for example, document photography lost its primary function, to inform

people, and gained the status of art.

In

essence, voluntarily blurred images did not give any information. They were

thought to be useless, unusable, and later with the pictorialists, artistic.

How did the blur, first considered as artistic and assimilated with art

photography, progressively become also associated with document photography?

If any picture acts as a document in itself,

showing for instance how people dressed, the practice of document photography,

that is to say photographs to report a fact or an event, increased during the

20th century. The expansion of newspapers, magazines and publicity

generated this practice. This idea of reporting facts, translating a pure

reality as it were, emerged with dissident photographers of the Linked Ring

Brotherhood and the pictorialist wave such as Stieglitz in the U.S.A. and

Frederick H. Evans in England.

III.

B. 2. a) Pure Photography

A blueprint of documentary photography is

apparent in the work of British photographer Frederick H. Evans who specialized

in architectural pictures. In his speech at his exhibition in the Royal

Photographic Society in London in April 1900, Evans introduced the idea of

‘pure photography’ as another goal of pictorial photography. Because he said he

was not at ease and good enough with the gum-bichromate process and

manipulations, he advocated a return to the negative as “the all-important

element”[7]. “Plain prints from plain

negatives is”, he explained, “pure photography”[8]. He detached himself from

a certain vision of the artist photographer “able to use pencils or brushes”[9] which was closer to the

painter. He continued,

“I should deprecate, and most strongly, this

freedom in control and dodging and altering; it leads one away from the

essential value of pure photography, its convincing power and suggestion of

actuality.”[10]

In

the same way, in 1904 American art critic Sadakichi Hartmann (1867-1944)

expressed,

“I do not object to retouching, dodging or

accentuation as long as they do not interfere with the natural qualities of

photographic technique. Brush marks and lines, on the other hand, are not

natural to photography, and I object and always will object to the use of the brush,

to finger daubs, to scrawling, scratching and scribbling on the plate, and to

gum and glycerine process, if they are used for nothing else but producing

blurred effects.”[11]

Some photographers demonstrated that all

pictorialist artifices were, in fact, twisting the nature of photography; that

they were altering the very qualities of photography. They were thus for a

return of pure photography and its own properties: a well exposed negative and

print. Photography should now refer to itself

and not to painting.

This idea was promoted by Frederick H. Evans

who did not care about fuzziness but noticed that

“there are no sharp lines anywhere and yet no

sense of fuzziness: at close vision the image is of course distinctly

unsatisfactory as regards pure definition: but at a proper distance there comes

a delightfully real, living sense of modelling that is quite surprising, and

most grateful and acceptable to the eye.”[12]

In

the case of Evans’s photographs, the very slight fuzziness was more linked to

the transfer from a negative image to a positive image, which implied a lack of

precision rather than an open blur, not to mention the imperfections of lenses.

Besides, Evan’s subjects were closer to

document photography than to art photography as Pictorialism suggested. He was

mostly interested in lines, figures and contrasts in architecture; and reported

the beauty of architectural structures. In the quest of form, Evans is closer

to Paul Strand (1890-1976) or Edward Weston (1886-1958) for instance.

Furthermore, his photographs were documentary in the sense that his subject was

documentary. He took a lot of pictures of English and French cathedrals and as

doing so, reported the shape but also the state of these monuments. Evans’s

photographs are documentary photography in a quest of aesthetic.

As

far as the use of blur is concerned, document photography shifted the notion of

blur to a new level. As photographers took documentary pictures and blur was unfortunately

reintroduced with either the camera shake or the movement of the subjects, it

moved away from its purely artistic quality. New practices entailed new visions

of the blur.

III.

B. 2. b) A documentary blur

Despite the fact

that the period in question does not cover document photography which was

mostly initiated by Americans like Lewis Hine (1874-1940) or Jacob A. Riis

(1849-1914) and other photographers like Eugène Atget (1857-1927), I looked at

a selection of English photographers which were at the very beginnings of

document photography and related them to a new perspective of blurred images. Ultimately,

I came to see British war photographer Larry Burrows (1926-1971) as the utter

embodiment of documentary photography.

At the 5th

International Congress of photography which took place in Brussels in 1910 a

definition of the document image was brought forward:

“Une image documentaire doit pouvoir être utilisée

pour des études de nature diverse, d’où la nécessité d’englober dans le champ

embrassé le maximum de détails possible. Toute image peut, à un moment donné,

servir à des recherches scientifiques. Rien n’est à dédaigner : la beauté

de la photographie est ici chose secondaire, il suffit que l’image soit très

nette, abondante en détails et traitée avec soin pour résister le plus

longtemps possible aux injures du temps.”[13]

With regard to the

actual documentary photographs and especially the very few shots taken in the

concentration camp of Auschwitz-Birkenau by the Sonderkommando in 1944,

reproduced in Georges Didi-Huberman’s book, Images

malgré tout published in 2004, this definition does not seem appropriate.

Apparently, blurred images do correspond with document photography.

Photographers unknown, Auschwitz-Birkenau, Poland, 1944

Early documentary

photography can be found in the work of major English photographers like Roger Fenton

(1819-1869) or David Octavius Hill (1802-1870) and Robert Adamson (1821-1848). In

the 1840s, in their workshop in Edinburgh, Hill and Adamson, respectively a

painter and a chemist, specialized in genre scenes and gathered a substantial

amount of prints depicting everyday life in Victorian England. In 1855, at

Prince Albert’s instigation Roger Fenton took pictures of the Crimean War to

offset the general unpopularity of the war. He was thus considered as the first

official war photographer. Similar studies can be found in the work of Frank

Meadow Sutcliffe (1853-1941) who only focused on the life of his hometown,

Whitby, in North Yorkshire; but also in Horace W. Nicholls (1867-1941) who

covered the Boer war (1899-1902) in South Africa and worked for the Imperial

War Museum; or in Paul A. Martin (1864-1942), French-born photographer whose

parents fled to England in the wake of the Franco-Russian war, who worked on

London’s life, mostly at night by gaslight.

In the middle of

the 20th century, documentary photography boomed through weekly

publications. Larry Burrows is representative of this period.

Larry Burrows, Near Dong Ha, South Vietnam, 1966

U.S. marines recover a body under fire during the battle for Hill 484

In Larry Burrows’s

picture entitled for Life magazine, “Near Dong Ha, South Vietnam”, blur filled

half of the right hand side of the picture and the four corners of it. The

faces of American soldiers are distorted, trapped in action. As soldiers were in

a highly urgent situation - they are holding a dying soldier - owing to the

fact they are running and Larry Burrows’s attempt to capture the moment the

camera could not be kept steady. Blur is not voluntary but exposes the idea of

instability, action, and thus embodies photo reportage. The emergency of the

situation echoes Robert Capa’s blurred pictures of the landing of the American

troops on Omaha Beach in Normandy in 1944. There is no time to take into

account the different parameters of the shot. Reporters just had to shoot

pictures before the moment was gone.

Through questioning

blurred images in document photography, it is obvious that blur is not linked

to control and aesthetic quests anymore, but to a total loss of control and instantaneity.

This loss of control over the real is not related to an altered real, as was

considered under the Pictorialists, but a real which is escaping and slipping

out from the hands of man. The real does not correspond to mental projections

of the artist but, in document photography, is associated with a real beyond.

In other words, the man is no more an agent of the real but, in the grip of the

real.

In that sense, in the document practice of

photography, I would regard blur as an action

blur. The action blur is either derived from the shake of the camera operator,

from the movement of the “reference field” or from a lack of optical adjustment

(focus) when taking the picture, due to the emergency of the situation.

[1] Michel Frizot, « Une autre

photographie, les nouveaux points de vue », p. 387-398, quoted in Michel

Frizot (dir.), Nouvelle Histoire de la

Photographie, Paris, Bordas, 1994, chap. 23, p. 390

[2] Alvin Langdon Coburn, “The Future of Pictorial Photography”, 1916, quoted

in Beaumont Newhall, Photography: Essays

and Images, New York, The Museum of Modern Art, 1980, p. 205-207

[3] Ibid. , p. 205

[4] Ibid. , p. 207

[5]

Alvin Langdon Coburn in a letter to Beaumont Newhall, dated April 11, 1947, is

quoted in Beaumont Newhall, Photography:

Essays and Images, New York, The Museum of Modern Art, 1980, p. 204

[6]

Aaron Scharf, Art and Photography, London, Penguin Books,

1986, p. 227

[7]

Frederick H. Evans, “On Pure Photography”, 1900, quoted in Beaumont Newhall, Photography: Essays and Images, New

York, The Museum of Modern Art, 1980, p. 181

[8] Ibid. , p. 180

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid. , p. 181

[11] Sadakichi Hartmann, “A Plea for Straight Photography”, 1904 is

quoted in Beaumont Newhall, Photography:

Essays and Images, New York, The Museum of Modern Art, 1980, p. 187-188

[12] Frederick H. Evans, “On Pure Photography”, 1900, quoted in Beaumont

Newhall, Photography: Essays and Images,

New York, The Museum of Modern Art, 1980, p. 184

[13] A. Reyner, Camera obscura, cité dans Ve Congrès international de

photographie, Bruxelles, 1910. Compte rendu, procès verbaux, rapports, notes et

documents publiés par les soins de C. Puttemenas, L. P. Clerc et E. Wallon, Bruxelles, Bruylant, 1912, p.72,

quoted in Molly Nesbit, « Le Photographe et l’Histoire Eugène

Atget », p. 401, is quoted in Michel Frizot’, Nouvelle Histoire de la Photographie, Paris, Bordas, 1994, chap. 24

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F97%2F73%2F133098%2F56684137_p.gif)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F21%2F13%2F133098%2F6437564_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F09%2F98%2F133098%2F6437899_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F27%2F46%2F133098%2F6438408_o.jpg)