Paradoxically, it seems that while photographers

were conforming to a pictorial vision, as Cameron did, they were at the same

time calling it into question as they were essentially questioning the

relationship between photography and painting. The British landscape

photographers George Davison (1854-1930) and Alfred Horsley Hinton (1863-1908)

sought to assert their distinctive photographic identity. Later they came to be

associated with the photographic and aesthetic movement called Pictorialism.

II. A. 2. a) George Davison: a naturalistic and

impressionist use of the blur

Both photographers instilled

impressionist and ethereal atmospheric effects in their pictures and both of

them worked on landscapes as their major subjects. As Davison stated in his

paper to The British Journal of Photography

in September 1889,

“It is not in man,

even in f.64 man, to overlook the unnaturalness of joinings in photographic

pictures, and the too visible drawing-room drapery air about attractive ladies

playing at haymaking and fishwives.”

Davison was in

agreement with Peter Henry Emerson’s rejection of Cameron’s pictorial portraits.

However, he did appreciate Oscar G. Rejlander and Henry Peach Robinson’s work

on prints made up of pieces of different negatives. He was against Robinson’s

main idea that the essential characteristic of photography was the use of focus

in order to achieve complete accuracy and sharpness. He also followed the steps

of Emerson and his theories upon photography which favoured a naturalistic

point of view on subjects, usually preferring taking picture of landscapes,

rural and seaside scenes.

Nevertheless,

Davison chose a different path concerning the use of focus. He preferred a

general soft focus rather than Emerson’s idea of a selected focus to set a

general idea of nature. He wrote in 1891 that “plus la photographie se révèle capable de

traduire une appréhension directe de la nature, plus elle peut influer sur la

sensibilité esthétique“.

In order to reach

this idea, he used a pinhole camera to produce soft focus pictures. One of his achievements

is the picture entitled The Onion Field

of 1889. The picture depicts an isolated farm which stands behind a vast onion

field. The human presence is introduced with smoke going out of a chimney and some

washing hanging out in the courtyard.

Opposing contrasts,

from the dark areas of the forest behind the farm to the foot of the onion

field in the foreground and light areas marked by the top of each single plant

of onion, one of the roofs of the houses which compose the farm, the drying

clothes and the sky, the overall image gives a feeling of light reflecting

differently, bringing out the shades of light, but largely absorbed by the

landscape.

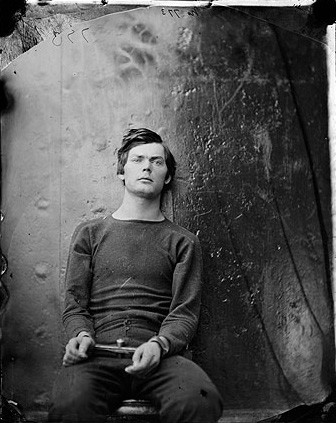

George Davison, The Onion Field,

1889

The picture

presents all the characteristics of impressionism. The perspective is flattened

by the use of soft focus due to the absence of lens in the pinhole camera.

Nothing in particular stands out. We are more under the “impression” of a

general landscape since the onion field mingles with the old farm situated in

the background. Accuracy of figures, though distinguishable, disappears to the

benefit of a “sensitive” apprehension on the general landscape. Davison

captured and emphasized the essence of the subject rather than its

details.

The Onion Field is

closer to the memory of an onion field rather than an accurate representation

of an onion field. Soft focus establishes the idea that what matters the most is not the

onion field itself but “the idea of an onion field”. Talking about pinhole cameras, Michel

Imbert said, “C’est le cerveau qui voit, ce n’est pas

l’oeil”.

This idea is

confirmed by the absence of lens, which usually stands for the human eye in the

optical mechanism of a camera. Therefore, the information given - a field of

onions - is interpreted by the pinhole camera - a fuzzy field of onion - which

can be compared to the human perception. It reinforces the fact that seeing is

always an interpretation. As Michel Imbert

put it,

“ Quand je regarde le monde qui m’entoure, je le

regarde avec mes yeux, c’est à dire mes désirs, mes craintes, mes propres

idées, mais lorsque je le regarde tel que représenté sur une photographie,

c’est à travers les yeux et l’esprit du photographe qu’il m’apparaît.“

The impressionist

photograph by Davison emphasizes his interpretation of a rural scene. A focused

representation of that onion field would have been a basic representation of an

onion field but the use of soft focus shows the idea of going beyond strict

reality, pure description or the science of appearances. Citing impressionist painters like Claude

Monet, Davison emphasizes the human perception of the real, in opposition to a

strict depiction of the real. He allows representation to go back to its

source. That is to say that, in representation, whether it is photographic or

pictorial representation, the major interest is not the real – the subject –

but what we understand of it and how we perceive it.

II. A. 2. b) Alfred Horsley Hinton: a purely

impressionist use of the blur

In the same way,

Alfred Horsley Hinton only focused on impressionist landscapes. Though he died

quite young, aged 45, he is one of the most brilliant landscape photographers

of English pictorial photography. Unlike Davison, he did not care about making

a direct print and liked to work on negatives. He usually composed his

photographs by working on several negatives, assembling them – what Davison mentioned

as “unnatural joinings”

- and often drew on them. In the end, he obtained one single and original

print. He was probably taught by Ralph Robinson, the son of Henry Peach

Robinson when he was working at Robinson’s workshop at the beginning of the

1890s.

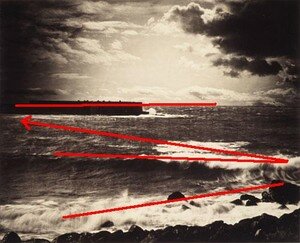

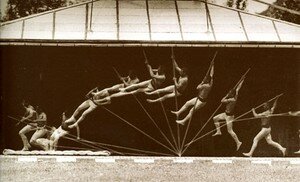

Alfred Horsley Hinton, Hymn, 1895 – Fig. 1

All of his

landscapes are English landscapes and his particular feature was to entitle his

photographs allegorically. His photographs Fleeting

and Far, Beyond and Rain from the Hills were both published in 1905 in Alfred

Stieglitz’s revue Camera Work

(1903-1917).

Hinton ran the London

revue Amateur Photographer and

supported pictorial photography until his death in 1908. His passion for

pictorial and impressionist photography reveals itself in his photograph Hymn taken in 1895 (fig. 1).

A pond, surrounded

by a forest in the background and a moor in the foreground, reflects the light

of a cloudy sky. Some dark and light areas from the sky echo in the pond. A row

of trees makes the transition between the earth and the sky.

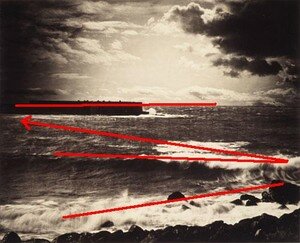

Gustave Le Gray, La Grande Vague, Sète, 1857 - Fig. 2

To study Alfred Horsley

Hinton’s picture, I would like to compare it to one of Gustave Le Gray’s

photograph he did in 1857 called La

Grande Vague.

Interestingly

enough, French photographer Gustave Le Gray (1820-1884) and Alfred Horsley

Hinton were both trained as painters and became photographers. Both pictures

associate two elements. The sky takes as much importance as the earth (fig. 1)

or the sea (fig. 2). We can recall Turner’s paintings when we observe the sky

of these pictures. Both skies are luminous and dramatic and reflect the watery

elements. Both photographers worked on two separate negatives, one for the sky

and one for the earth.

What is blurred in

Le Gray’s picture is the motion of the wave splashing the rocks, whereas in

Hinton’s it is the vegetation. In both pictures, we can sense the action of the

wind which is implied by the dramatic sky. If Le Gray faces a big wave, as the

title of his picture suggests, Hinton’s pond shows wavelets on its edge. It is

interesting how the slight blur of each picture is linked to the notion of motion

and time of exposure. In Hinton’s landscape, it gives a dreamy and impressionist

idea of a British landscape whereas in Le Gray’s picture, it emphasizes the

very action of the wave splashing the rocks of the quayside at the city of

Sète.

Besides, the

structure of both pictures is very similar. The skyline is broken by the forest

in Hinton’s (fig. 1) and by the dock in Le Gray’s (fig. 2). If we compare the

lines of sight, we can see that they both start from the bottom of the right hand

side of the picture and point to the middle left hand side. In the foreground,

the row of rocks (fig. 2) echoes to the line of the moor (fig. 1). Parallels

can be drawn between rocks and the dock (fig; 2) and the beginning of the pond

and the background forest (fig. 1).

As for the titles

of the pictures, Gustave Le Gray’s seascape has got a descriptive title whereas

Alfred Horsley Hinton entitled his picture Hymn.

This may refer to what the landscape recalls to him. Hinton chose an evocative

caption, drawing an interpretation of his subject. Le Gray chose a descriptive one.

While Le Gray’s picture only refers to itself, Hinton’s approach of the

landscape invites us to reflect upon another image, picture or sound we have in

mind, drawing a line between photography and history of art or photography and

music for instance.

Thirty-eight years

after The Great Wave by Gustave Le

Gray, photography had evolved, experiencing new techniques and visions among

those who practised it. Neither picture is more beautiful or artistic than the

other but they demonstrate a different approach to photography. Impressionist

vision is what characterised Hinton and Davison’s landscapes. They deeply

related to the artistic trend of the end of the 19th century, and in

particular to painting with the Impressionist movement. It is quite interesting

to notice that it was French photographer Nadar who first presented the

Impressionist painters in his workshop, boulevard des Capucines, in 1874.

Michel Imbert,

« C’est le cerveau qui voit, ce n’est pas l’œil », p.55, quoted in Jean-Marie Baldner & Yannick Vigouroux, Les Pratiques Pauvres, du sténopé au téléphone mobile, Paris,

Isthme éditions, 2005

B. The

Theoretical Blur

With regard to the focus debate, Peter Henry

Emerson was the first photographer to support and draw up a theory out of the

use of a partial blur. He developed an aesthetic vision that he claimed was naturalistic.

After Cameron’s spiritual blur and Davison and Hinton’s impressionist

fuzziness, Emerson threw himself into pictorial photography which he proposed

to redefine.

II. B. 1. a) Peter Henry Emerson:

a scientific approach of pictorial photography

Peter Henry Emerson (1856-1936) was a brilliant

medical student who abandoned his career as a physician for the sake of

photography. He sought a scientific founding to art photography, and made a

dashing and revolutionary entrance in the photographic world when, as an

introduction to his aesthetic approach of what photography should be, he harshly

criticized all the emblematic figures of pictorial photography and

pre-Raphaelites.

In his lecture to The Camera Club of London, in March 11, 1886, though unnamed, he

referred to art critic John Ruskin, who influenced pictorial photographers like

Cameron and Rejlander, in those terms:

“One of these spasmodic elegants of Art

literature has made it a point to scoff at any connexion between science and

Art, and has flooded the world, in beautiful writing in which his power lies,

with dogmatic assertions and illogical statements.”

In the same way, he was not afraid to target photographer

Henry Peach Robinson’s book, entitled Pictorial

Effect in Photography (1869),

“a senseless jargon of quotations from literary

writers on Art matters, a confused bundle of lines which take all sorts of

ridiculous directions (…) contain[ing] the quintessence of a blend of literary

fallacies and Art anachronism”

Having

established his full disagreement with former pictorial photography, and

adopting the ideas of Hermann von Helmholtz, who explored the mechanics of

human vision, Emerson tried to find a new base to photography. He said, “we

[photographers] can never equal painting; but all other branches of pictorial

Art we are able to surpass”. “Painting alone”, he continued, “is our master”. His whole point was to represent

as true as possible the impression of Nature on the human eye. The real was

supplanted by the perception of the real. His approach was called naturalistic.

To

reach this idea of a naturalistic approach, he advised photographers to go

outside their studios and workshops and photograph real people in their natural

environment. He dismissed the contrived and posing costumed models of Victorian

society.

As regards the use of focus, Emerson explained

his views in his book, Naturalistic

Photography for Students of the Art, twenty years after Robinson’s, in

1889. He advised a focus with judgement, a slight out of focus,

“not [to] be carried to the length of

destroying the structure of any object, otherwise it becomes noticeable, and by

attracting detracts from the harmony, and is then just as harmful as excessive

sharpness would be. (…) Nothing in nature has a hard outline, but everything is

seen against something else, and its outlines fade gently into that something

else, often so subtlety that you cannot quite distinguish where one ends and

the other begins. In this mingled decision and indecision, this lost and found,

lies all the charm and mystery of nature.”

His

textbook was described as “a bombshell dropped in a tea party” and resulted in much

criticism. Robinson claimed that “healthy human eyes never saw any part of a

scene out of focus”. And Emerson replied “I

have yet to learn that any one statement or photograph of Mr. H. P. Robinson

has ever had the slightest effect upon me except as a warning of what not to

do.” As a result, some

photographers followed Emerson’s point of view on out of focus and started to

shoot soft focus photographs, sarcastically called by others “fuzzygraphs”.

The debate over focus was a very tricky and

impassioned one in 19th century British photography. Emerson had

made a vehement protest against the former genre of pictorial photography, yet

the photographical world continued to subscribe to a pictorial composition as

the photographs of the period remained very similar in framing and composition

to painting. The combination of these

two factors initiated a new way of making picture. Emerson’s style stands

in-between pure photography – or ‘straight photography’ as Sadakichi Hartmann stated

- and pictorial photography.

II. B. 1. b) Peter Henry Emerson: the obsession of

focusing like the eye

In my study of Emerson’s naturalistic

fuzziness, I will compare his photograph entitled A Stiff Pull (1888) to Jean François Millet’s painting called Les Glaneuses (1857) presented in the Musée

d’Orsay.

Peter Henry Emerson, A Stiff Pull, 1888

Jean-François Millet, Les Glaneuses, 1857

Jean François Millet (1814-1875) was one of

Emerson’s big influences. He actually referred to him in is Photography, A Pictorial Art among other

painters such as John Constable (1776-1837) and Camille Corot (1796-1875). As a

matter of fact, Millet and Corot’s work had been exhibited in London in the

1870s.

A

Stiff Pull was published in the

book Pictures of East Anglian Life in

1888 and presented a lot of folkloristic studies. Two horses are dragging a

plough while a farmer is digging a furrow in fallow land. Gravel is scattered

over the surface. A cloudy sky opposes the sloping ground in equal proportion. The

scene is taken from behind. The horses stand in the centre whereas the ploughman,

who is wearing a hat, lies in the foreground on the left hand side of the

picture.

In

Jean François Millet’s picture, Les

Glaneuses, gestures and details in the picture are absorbed in the action.

The hands and face of the female gleaners are coarse and roughly done. Their

shoes almost merge with the colour of the land. In the same way, the colour and

shades of the sky reminds the brown and yellow tones of the field. A feeling of

blur and lack of accuracy prevail.

Similarly, a general look at Emerson’s picture shows

that it does not give any sharp vision of the rural scene he photographed. The

horses and the top of the ploughman’s body stand out of the skyline level but

the overall greyness of the ground corrupts the living elements. In his effort,

the ploughman seems disproportionate and deformed. Besides, the motion of the

effort sets the general fuzziness of his body.

However,

a closer look at Emerson’s pictorial picture may change our first impression. In

spite of a general soft focus, some parts appear to be focused and sharp. In

fact, if the left leg is blurred by the pull of traction, the other one, the

stiff one as the title says, is sharply focused. Even if it is difficult to

distinguish the ploughman’s right shoe, deepened in the gravelled ground, we

can observe that around this shoe all the ground and stones are totally focused.

Therefore, Peter Henry Emerson, through the title of his photograph, pointed

out the area that the viewer should look. With the caption, he actually indicated

where the viewer should in turn focus.

In The

Amateur Photographer, January 1890, D. Habord described the picture as

such,

“An awful abortion representing a man plowing

up-hill with a pair of horses. The man’s foot was as long as the horse’s head

and the whole picture was gloriously so ‘naturalistic’, i.e., ‘fuzzy’ or

‘focused with judgement’ that it was denounced as an imposture.”

Nonetheless, the plate received a silver medal at The Amateur Photo Exhibition in London in 1886.

Setting the pictures of Emerson in the history of

photography, he appears as a pioneer photographer. Although he abandoned his

beliefs that photography was an art in 1891, after he was told by scientists

that control of tones by development was impossible, he was the first

photographer to have linked up science and art, the document and art

photography. With his care of a naturalistic subject, framing and hypothesis on

what focus should be, he seemed to have brought in the very beginnings of

social photography.

In

his ideal of representation, Emerson tried to gather both the Truth and the

Beautiful, as Baudelaire opposed in these terms two contradictory aspects of

art in his speech of the Salon des Beaux-Arts of 1859. A true representation was

achieved by the choice of subjects and a beautiful one thanks to the art of the

photographer. Following the tradition of pictorial art, a concern in framing,

the rendering of the light in its shaded tones (Photography, a Pictorial Art) and through the use of blur Emerson

banished the idea of a commercial photography and its primary function as a

document.

In the 1880s, through on-going debates and

discussions upon the use of blur, photography had reached the status of art in

photographers’ mind. Painting and photography were easily comparable and similarities

were drawn between the two. Photography little by little had gained

credibility. Now sharing a mutual ground with painting, through combining aesthetic and mastery, photography was

waiting for its independence and recognition from a larger audience. Even

though photographs had been exhibited since the very beginning of the 1850s and

photographic societies flourished, photographers wanted to offer their art a

‘room of its own’, to borrow Virginia Woolf’s words in another context. As

such, a group of photographers decided to set an example and ventured into the

prospect of photography as an art.

II. B. 2. a) The Linked Ring

Brotherhood: a showcase to blurred photographs

In 1888, the first hand camera was released on

the market by George Eastman’s company Kodak. A year later, photographic film was

made of celluloid and mass produced. A new photographic industry developed and

specialized in processing film rolls and printing. Consequently, there was no more

need to have a special room in the house dedicated to photography, no need to

manipulate and buy expensive chemicals or glass plates and no need to possess

knowledge to make meticulous hand-prints. It was thus a major breakthrough in

the evolution of photography. These great improvements introduced a new

approach in framing pictures and allowed photographers to explore their

environment, leading at the beginning of the 20th century to

documentary and street photography. As a result, a larger population could now

access photography; a population which, on the whole, held no regard for

photography as an art.

Owing to the fact that photography was now

available to a new social class, it was no more the privileged pastime of a

certain elite called the amateur photographers. More and more images were being

produced, sold and reproduced. More and more photographs illustrated newspapers

for example. In view of the democratisation and industrialization of the medium

and out of fear that good taste and art would be crushed by popularization,

some amateur photographers distanced themselves and got together to discuss representation

and art photography.

In 1891, the first exhibition of art

photography took place in Vienna. It was initiated by the German photographic

society Kamera Club. Some British amateur photographers from the Royal

Photographic Society, who felt disenchanted and oppressed by the majority of

photographers who were basically technologist photographers, complained that

their work was not recognized and decided to break away and form their own

collective.

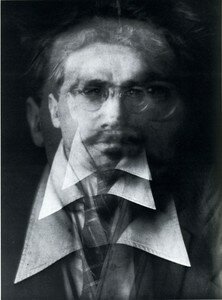

With regard to the American Civil War of the

1860s, they later claimed themselves to be photo-secessionists, as American

Alfred Stieglitz’s speech suggested in 1903.

Alfred Stieglitz claimed that the

photo-secession was accomplished

“(…) to register their [photographers] protest

against the reactionary spirit of the masses. This protest, this secession from

the spirit of the doctrinaire, of the compromiser, at length found its

expression in the foundation of the Photo-Secession. Its aim is loosely to hold

together those Americans devoted to pictorial photography in their endeavour to

compel its recognition, not as the hand-maiden of art, but as a distinctive

medium of individual expression.”

Under the impulse of Alfred Maskell, British ‘secessionists’

assembled and founded the Linked Ring Brotherhood in 1892. This new society, whose

founder members were Alfred Maskell, H. P. Robinson, Lionel Clark, George

Davison, Henry Hay Cameron (Julia Margaret Cameron’s son) and Alfred Horsley

Hinton, declared itself to be the standard bearer of art photography in

England. The name of the Linked Ring was chosen to symbolize the unity of its

members.

The Linked Ring Brotherhood welcomed

international photographers who had also broken away from the mainstream -

seceded - and adopted new members such as British photographers Frederick

Evans, Alvin Langdon Coburn and Frank M. Sutcliffe; American Baron Adolf De Meyer,

Alfred Stieglitz, Edward J. Steichen, Gertrude Käsebier and Clarence H. White;

French Robert Demachy and Constant Puyo; and German Heinrich Kühn, and Theodor

and Oscar Hofmeister.

To promote art photography, the aims of the

Linked Ring were threefold. First, they held annual exhibitions from 1893 to

1909. They called them “salons”, a name deliberately borrowed from the world of

painting. Second, they published portfolios, photoengravings and photography

revues. Alfred Horsley Hinton took over the editorship of The Amateur Photographer in 1893. Finally, they spread the

Pictorialist ideas which expanded with the creation of other international

photographic societies such as The Photo Club of Paris and The Photo-Secession of

New York.

Following the example of painting, once thought

to be a purely mechanical process, they sought to demonstrate photography’s

uniqueness. From the dominant idea of photography as scientific, liberal and

opened to anyone emerged the

Pictorialist movement which encompassed all artistic photography, whether it was

impressionist, naturalistic or symbolist.

II. B. 2. b) The Pictorialist Movement:

a claiming of blur

Pictorialism was considered the first

photographic movement.

It took place between 1888 and 1918, as the

first French exhibition on the Pictorialist movement, entitled “La photographie

pictorialiste en Europe 1888-1918”, presented in the city of Rennes this year

suggested. Pictorialists questioned

the nature of the real and the nature of photography. In 1918 Pictorialism gave

way to another art and literary movement, the Dada movement.

The name ‘pictorialism’ had long placed

photography alongside painting whereas their relationship to one another was

ultimately different.

Marc Mélon established the relationship between

photography and painting as follows,

“Il

ne s’agit pas comme beaucoup l’ont pensé, d’un strict mimétisme entre une

photographie complexée et une peinture supérieure devenue le modèle

inaccessible de la première. Il s’agit plutôt d’un rapport concurrentiel qui

pousse la photographie non à imiter la peinture, mais à s’élever à son niveau

et, sur un pied d’égalité, à revendiquer le même prestige. C’est le grand

projet du pictorialisme : considérer la photographie comme un des

beaux-arts.”

Mélon continued,

“La présence

du mot ‘picture’ dans la dénomination anglaise du mouvement rappelle quel était

son objet initial : faire connaître la photographie comme image parmi les

autres images.”

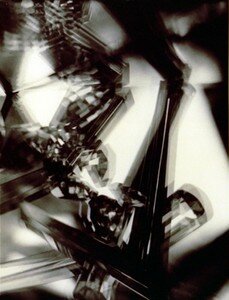

So as to make photography’s name among the

field of other images (painting, drawing, etching, woodcutting…), the pictorialists

advocated complex processes which allowed interpretation and subjectivity. Working

on the negatives and prints; using salts, gum-bichromate, charcoal or inks to

reproduce this interpretation of the real were very common. They played with

various textures of papers and favoured drawing on materials. They scratched,

coloured and altered negatives and prints. They explored all the possibilities

of the photographic object(s) and thus photography itself. All these processes led

to the creation of single prints, which illustrated that a photograph could be

as original and unique as a painting. Photographers were no more operators but

creators, artists and authors. They succeeded in manipulating and transcending the

real, as painters had already done.

Clearly, when negative images were not already

blurred, all these manipulations eventually triggered off blur on the general

aspect of the accomplished piece. Hard outlines were softened; sharpness and

photographic grain stumped by the hand of man, obsessed by the making of

artistic print.

If out of focus already existed with the

manipulation of the camera – obscura or not –, it is only with the invention of

photography in 1839 and with the appearance of the Pictorialist movement that

an aesthetic of the blur and subsequently, a form of blur ideology – derived

from that regular and constant use of it – emerged in the 1880s.

The flaw of the image – blur – was used as an

asset to show that photography was not a mechanic tool but an aesthetic

pleasure; a proof that photography’s main function was not strict reproduction

but the art of reproduction. The flaw was thus integrated by the pictorialists

in order to make the audience admit that photography was an art.

As with any great artistic movement, pictorialists

needed a manifesto. They found it in Robert de la Sizeranne’s article “La

Photographie est-elle un art?” published in La

Revue des Deux Mondes in 1897.

On the aesthetic of blur, Robert de la

Sizeranne concluded,

“Le flou est justement au net ce que l’espoir est à la satiété. Il

est l’équivalent, en art, d’une des choses les plus aimées de la vie :

cette délicieuse incertitude d’une âme où déjà pénétra l’espoir et où

l’assurance n’est pas entrée encore ; où le désir qui commence

d’apparaître comme réalisable n’a pas cessé d’être avivé par les obstacles à sa

réalisation ; où tout se promet et où rien ne se donne, où tout se devine

et où rien ne s’avoue ; où les figures et les paysages et le ciel et la

terre et l’amour même apparaissent selon les incertaines suggestions de l’aube,

et non selon la sèche définition des midis…”

Robert de la Sizeranne’s laudatory speech on the use

of blur shows how significant it was for the pictorialists and mostly how blur

was a bridge between photography and art. It was a springboard to elevate

photography to the level of art. In his speech, the blurred image entails other

images and on top of that, feelings. Robert de la Sizeranne talks about

uncertainty, promise, hope and desire. Blurred photographs prompt reactions, emotions

which are the ultimate purpose of art. He says blur embodies “la grâce,

l’indécision, la fraîcheur, ce que les artistes recherchent d’abord” He puts into words his

impressions regarding blurred photographs. By doing so, he accomplishes the

work of an art critic and therefore legitimates photography as art.

As

a consequence, a new market opened to photography. Photographs, promoted by

magazines and revues, were reproduced in postcards for example. Photographs

were widely exhibited by societies, like in the universal Exhibitions of Paris

in 1889 and 1900, of Anvers in 1894 or of Liège in 1905. They also connected

with galleries and sold prints. In 1896, the curator of the National Museum of

the United States of America dealt the first purchase of photographs as works

of art for a sum of $300. The same year, Belgium opened a photographic Museum.

Photographs became cultural products.

Pictorialism

succeeded in offering photography a room in the artistic world. Along with

other processes, fuzziness enabled photography to find a place among other

images.

Little by little, artistic pictures became the

ones only produced by the pictorialists. A very few examples aside, like

Frederick H. Evans for instance, the majority of pictorialists adopted

fuzziness as a necessary condition of their work. “[Les]

effets artistiques ne s’obtiennent, en géneral, qu’aux dépens de la minutieuse

et scientifique définition des détails”, wrote Robert de la Sizeranne. This sentence completely defines the work of pictorialists

but paradoxically announces their inability to evolve.

For the pictorialists, blur became the artistic

value and consequently sharpness became the scientific one. Sharp images were the

proof of strict representation; a representation without any interpretation,

thus no artistic view could be derived from it. Science was facing art and blur

sharpness. Sharpness was thought to undermine art photography. On account of

their endeavour to promote art, pictorialists refused science and focused

images.

Nevertheless, scientific progress reduced the time

of exposure under the measure of the second which evidently entailed sharpness.

While legitimating blurred pictures as an art, at the same time photographic

processes, elements and materials were evolving and thus making photography

more accurate. Cameras were getting smaller and easier to manipulate. Lenses

were more and more accurate and sophisticated. Films and papers were improving

in levels of quality, definition and finishing. In fact, photographic images

were to become more and more accurate and sharp.

In 1908, the majority of photographs presented

in the annual Linked Ring exhibition were Americans. As a protest, British

photographers, whose work had been rejected by the Selecting Committee, organized

a “Salon des Refusés” which took place in The Amateur Photographer’s editorial

office. As a result, a lot of talented American photographers resigned from the

Linked Ring Brotherhood which eventually dissolved in 1909.

At the beginning of the 20th

century, new photographic aesthetics emerged and the goals of the Linked Ring

Brotherhood became somehow obsolete. Besides, photography was not English any

longer but mostly American.

Robert de la

Sizeranne, La Photographie

est-elle un art ? , La Rochelle, Rumeur

des Ages, 2003, p. 16-17